©WAMU 88.5 All Rights Reserved

Contact | Privacy Policy | Terms of Use

— a public media initiative to address the drop out crisis,

supported by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.

At the Tabard Inn in Washington, D.C., Christopher Feaster, 19, is just starting his shift as a host. He is dressed formally and strikes a professional tone as takes calls from customers.

“We do not take reservations in our bar and lounge area ma’am. It’s first come, first serve only,” he says to a customer phoning in. “No problem, have a good one, bye.”

He still has the perfect manners I remember from back when I first met him in 2012. He was a high school senior then and he stood up, shook hands and said “pleased to meet you” — he was considerably more polished than your average teenager.

Every year, I profile academically exceptional teenagers from the nation’s capital as they get ready to go to college. Like the majority of children in D.C.’s public schools, they are poor. Many have faced extreme challenges at a young age.

Christopher seemed in a lot of ways like the poster child for grit and determination. During much of high school, he and his mother were homeless and living in a shelter.

But he persevered. Despite an unstable home life, Christopher received high marks in high school, won every academic award imaginable and received a full-ride, four-year scholarship to Michigan State University. At the time, I thought that was beginning of a bright future for Christopher.

His mother, Nkechi Feaster, felt much the same way. She stops into the restaurant as Christopher works his shift.

Nkechi raised Christopher as a single parent. Their relationship, which was always so close, grew strained after he came back to D.C. in 2013. The reason? Christopher had dropped out after just a year at college.

For a long time, he wouldn’t tell his mother why he wasn’t going back to school.

“Why? Why? Why? Why? Why? I could not understand it. I could not understand it. All I can see is the opportunity in the trash,” she says.

She worries about how Christopher will survive in an economy where a degree is increasingly necessary. But for the most part, she keeps her fears to herself.

“Right now what I’m looking for is: Is he going to find a lesson from this? What is it going to be?” she says.

What is the lesson? What would cause so promising a student to drop out? How could Christopher’s time in college have turned out differently? And if a talented kid like Christopher can’t make it, what chance do other low-income students have? These questions bothered me more and more as I spent time with him.

As a nation, we’ve concentrated a lot on getting low-income students like Christopher Feaster into college. What we haven’t focused on is whether those students complete college.

Christopher’s story is far more common than I had thought. By some estimates, just one out of every four low-income students that attend college make it through to graduation day. The reasons, as it turns out, often have very little to do with money.

With Christopher, there was so much going on under the surface. When I first met him in 2012, he and his mother had been evicted from several apartments and were living in a homeless shelter. All of his belongings fit into two plastic boxes.

“I was always prepared in case my mom and I got evicted,” he said then. “For the most part, things stayed in containers, so all I had to do was store some trophies here, put some papers there, done. My room is packed up, perfectly ready to go.”

Christopher and his mother couldn’t afford to do laundry more than once a month.

“I would have to re-wear socks. They were white socks but they were so dirty that they were brown and sometimes they were starting to go black. I had to re-wear underwear because I didn’t have clean underwear,” he says.

Sometimes the stress of the situation got to be too much.

“If I felt like I was tearing up I’d go to the bathroom, I’d look at myself in the reflection, I’d be like: ‘OK Chris, calm down just breathe, just breathe,’” he says. “There was only one time where I slipped up and I actually cried in class. Tears were just falling down my face.”

Christopher and his mother now live in subsidized housing in Washington, D.C. The complex has blocks of buildings with iron grills on the windows and shards of broken beer bottles near the entrance. A resident sees me and shouts out to no one in particular: “Someone’s in the building. She’s either a Jehovah’s Witness or a social worker!”

I knock on the faded blue metal door, take a step back and wait. A red, black and green bumper sticker at my feet reads ‘No Jesus, no peace. Know Jesus, know peace’.

I knock again, louder this time and the door swings open. Christopher rubs the sleep from his eyes.

“Come in!” he says warmly. Christopher has put on a little weight since I last saw him. But otherwise he looks the same. His face is one big smile.

To understand Christopher, you have to understand his relationship with his mother. He often says they are “twins,” and he is very protective of her. Nkechi was 19 and had just finished her freshman year of college when Christopher was born.

She never went back for her second year.

“Did not have a job, did not have anything. I didn’t see a way for me to go back,” she says.

Nkechi has had a hard life. She was diagnosed with diabetes at 11, and has been physically and sexually abused. She’s also struggled with depression, and was laid off three times during the recession.

But even while Nkechi struggled to provide for Christopher, she always insisted that education was important.

“Homework was vital,” she says. “I went to every parent-teacher conference. If school is open, you’re going. So those last three days of school that were only half days? He was there, he was definitely there.”

She found a way for him to stay at the same elementary school even when they moved frequently and enrolled him into an after-school program in middle school. Christopher says she was single-minded in her focus.

“Since as far as I can remember, ‘Chris, you are not allowed to put anything before school … nothing. I don’t care if you only have 45 seconds of school, you’re going and you better come home and tell me something new that you learned,’” he says.

The basement apartment Nkechi and Christopher share is pretty stark — there’s not much furniture and a large tablecloth covers the windows in the living room because the blinds are broken. But it’s home.

Christopher still has one of the two large plastic containers that held all his stuff every time he and his mother were evicted.

He pulls out medals from competitions, cards from a high school counselor reminding him he was “capable of greatness” and a dizzying number of certificates.

“More awards of excellence, honor roll, high honor roll, high honor roll, a lots of awards. Recognition, participation, completion, achievement, outstanding performance, outstanding performance. It’s a lot of outstanding performance and high honor roll in this stack. Wow, I remember those days,” Christopher says.

And then, tucked away in a folder, he finds the letter that was going to change his life.

“What is this? Oh wow. I forgot about this: ‘Dear Mr. Feaster, Congratulations and welcome. I am delighted to inform you of your admission to Michigan State University for Fall Semester 2012.’”

That letter marked the end of Christopher’s long and intimidating process of applying to college. Navigating all that information can be confusing for anyone, but according to Caroline Hoxby — the Scott and Dana Baumer Professor of Economics at Stanford University — that is especially true for low-income students who are often the first in their families to go to college.

“I think there is a common mismatch between aspirations among American high school students and their knowledge of how to turn those aspirations into real, concrete plans,” Hoxby says.

A big problem, according to Hoxby, is that people just didn’t notice that completion rates were so low.

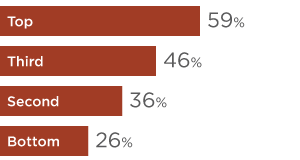

When you look at the numbers, less than 40 percent of full-time students graduate college in four years, and only about 60 percent finish college in six. If you factor in students who start at community colleges, those numbers are far lower.

Hoxby says people believe college is transformative and opens up all these opportunities.

“I think all of those things can be true, but the transformation is created by going through college and learning the skills that are necessary for college. I think our romantic idea was that simply showing up on campus was enough,” Hoxby says.

Low-income students face all kinds of obstacles before they even get to college. If they even apply, they often “under-match,” meaning they don’t even try for competitive colleges that meet their academic ability. Instead, they apply to less demanding schools, where there are fewer supports and less financial aid.

“So it’s not just the attend/don’t attend decision that matters, it’s really what sort of institution are you attending? That may seem like a subtle difference, but it’s not a subtle different. It makes a very big difference to college completion,” she says.

Money is another issue. Not only do low-income students worry about being able to afford college, they also often have to help provide for their family.

But it’s about more than that. In Christopher Feaster’s case, the two major barriers to college — access and money — had been taken care of. He attended a school called Hospitality High, which is designed to prepare students for jobs in the hotel industry.

At the school, Michael Cucciardo and Tiffany Godbout-Williams are looking at photographs of Christopher in old high school yearbooks. Cucciardo was his teacher and is now executive director of Hospitality High. Godbout-Williams held that position when Christopher studied there.

The school was an anchor in Christopher’s unstable life. It has just 150 students, so Cucciardo and Godbout-Williams knew him very well. They gave him a lot of basic supports, including uniforms, eyeglasses and travel vouchers to and from school.

And Christopher flourished. He organized school activities, started a mentoring club and was an academic superstar.

Teachers there helped students research different schools and apply for scholarships. They pushed students like Christopher to look beyond their present circumstances.

“We don’t set kids up to be successful if we continue to make excuses for them,” says Godbout-Williams. “A lot of what we did was be empathetic and loving and caring toward Christopher, but you know what, you’ve got to overcome this and continue to push.”

All that structure and support paid off. In the spring of 2012, Christopher was accepted into the hospitality business program at Michigan State University.

There’s a picture of Christopher in his black cap and gown, and they beam like proud parents. By graduation, he had received close to $200,000 in scholarships.

“The night of graduation he got the final award. There was an angel scholarship that Michigan [State] had secured for him, it was anonymous, like $18,000, it was a lot of money. And the cheer, oh my god! His mother jumped up in the aisle, it was amazing. I still get goosebumps over it,” Godbout-Williams says.

Both Cucciardo and Godbout-Williams say that, for them, it was a perfect moment where everything just seemed to come together.

“The thing that I think made me most happy and proud is he had lived up to his side of the agreement, did everything he needed to do and our organization and our partnerships, we were able to eliminate that financial barrier,” says Cucciardo.

In the fall of 2012, Christopher packed up his things and moved to East Lansing to start his program at Michigan State.

He quickly found that the success he enjoyed in high school did not, unfortunately, carry over to college.

“I thought with the effort I was putting in, I was like, yeah, I probably got an A or B. And I look at my class: C. What the hell?” Christopher says.

He became ill a few times and felt more and more overwhelmed. He spent a lot of time alone in his room. But when he came back home to D.C. for the Thanksgiving break, he told his mother everything was just fine.

Christopher’s high school principals, Cucciardo and Godbout-Williams, had kept in touch with him. But unlike his mother, they found out he was struggling.

“I woke up because I had a phone call from Ms. Hawkes. And she was like, ‘Yeah Mr. Cucciardo is here.’ I’m sorry, what?” Christopher says, recalling his surprise when his mentor at MSU told him his former school principals were on campus.

They had heard he wasn’t bothering to hand in homework anymore or even attending classes. They spent their own money to get on a plane to Michigan and speak to him.

“His face was absolutely priceless,” Godbout-Williams says, remembering with a laugh.

“And the first thing that happened when the three of us were all alone, Mr. [Cucciardo] looked at me and said, ‘Chris, what the hell is going on?’ And there are a lot of people in my life, who I can look them in the eye and tell them I’m doing fine, I can never tell a lie to Mr. C. I still consider him one of the biggest mentors in my life. He and Ms. Tiffany had earned the right for me to tell them the truth because they had put so much faith and effort into me, they deserved an explanation,” Christopher says.

Christopher told them about his poor grades, how much he worried about his mother, and his fears of not belonging.

“Why? Why? Why? Why? Why? I could not understand it. I could not understand it. All I can see is the opportunity in the trash.”

Nkechi Feaster, Christopher's mother, when she learned he wasn't going back to school

“I remember at the end of the conversation, we were all in tears,” Cucciardo says. “We were like ‘this is what we need to do going forward, we can’t change the past but this is what we need to do going forward.’”

They stayed for two days, met Christopher’s professors, sat in on his classes and set up a plan for him — all the structures they had used to help him be successful in high school.

“I walked away from that whole event thinking he’s still going to make it,” Cucciardo says.

But Christopher slid even further into depression and stopped answering texts or phone calls. He felt he had disappointed everyone.

“By then I had the mentality of it was too late, you’ve already screwed up enough to where there is no point, you literally cannot bring yourself up to at least pass. So I gave up. And that trickled down for the rest of the year,” Christopher says.

Christopher failed all his final exams and his GPA was 1.4. At the end of his freshman year, Christopher was told he would not be allowed back to Michigan State. He returned home.